Author: Dr. Ross Headifen (PhD)

Ross Headifen has a PhD in Mechanical Engineering and has 28 years of experience developing sustainable and environmental industry products. Ross is co-founder of landfill biodegradable plastics brand Biogone and environmental equipment supplier FieldTech Solutions.

Prior to 2018, plastic recycling in Australia for the most part involved packing up our recyclable materials, putting it in a container and sending it overseas, basically washing our hands of it. Then along came the Chinese Sword in 2018 and they stopped taking our plastic waste, and other neighbouring countries soon followed suit. Laws were introduced here to stop sending plastic waste offshore and it was proposed to deal with it here. Government targets were set up for recycling rates and for recycled content in plastic were listed. Then came the collapse of REDcycle, leaving many consumers who want to do the right thing, thinking, what do we do now?

We know Australia has a long way to go in getting our recycling systems right, particularly our plastic recycling. But firstly, let’s consider the myriad of problems associated with recycling of plastic.

There are several different types of base polymer plastic in common consumer use today, PET, LDPE. HDPE. PVC, PP being the main ones. For a high-grade recycled product, these materials cannot be mixed, but must be sorted first. That in itself is a huge challenge, who does this? Where is it done?

There are thousands of different additives mixed in with the base polymer in plastics, such as additives for plasticising, UV stabilisers, fillers, degrading, hardeners, anti-static, flame retardant and more. How do we think one piece of plastic recycled material can be mixed with another and to know the final properties?

There are also thousands of shades of colours added into plastics. A piece of red plastic cannot be recycled into a clear plastic item, or a blue piece into a red item. All of the colours must be separated out to make like products. A limited solution is for a black additive to be mixed with coloured recycled items to hide their colours and produce a black material. But how many black items do we need and how is this colour separation going to occur? Where in the recycling process would it occur?

We also have to consider the differences between recycling hard plastics versus soft plastics. They need to seperated, as their recycling processes are very different.

There is also very little incentive for people to recycle their plastic, and we need collection infrastructure in Australia to rapidly increase to reduce the 80% of plastic waste is going to landfill currently.

Assuming all the above could be addressed and turned into a viable recycling industry, what we also need is a review of the definitions being used for recycling as it is far from as simple as this one simple word sounds.

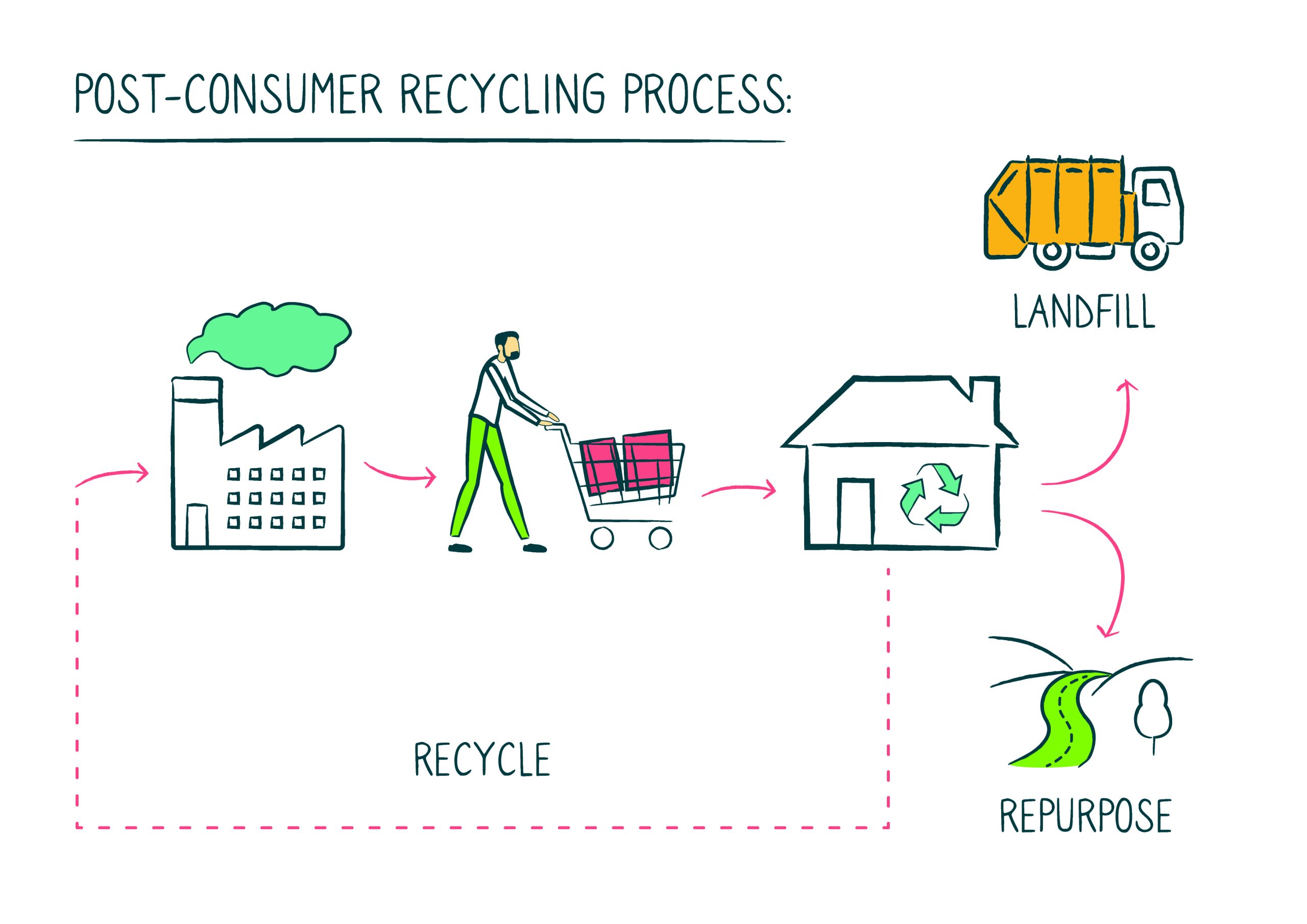

Recycling makes consumers feel better about disposal of packaging and end of life of products. In its purest form, recycling is where materials are used to make a product, the product is used by consumers and the material is sent back to be processed into further similar products. This is known as Post Consumer Recycling (PCR). This is the idea of the circular economy. Once enough materials are in the economy, there would be no further need for virgin resources to be sourced and used any more.

The use of how the word ‘recycled’ for plastics is being used these days, shows many variations. Very few of these achieve the goal of ‘recycled’ plastic that was used by consumers, then returned to plastic manufacturers. A lot of the time, the umbrella claim that marketers love to use, ‘Contains Recycled Plastic’ can be misleading to the consumer.

Most plastic waste is not recycled but repurposed by other industries into lower grade applications such as roads, concrete, outdoor furniture. What most consumers don’t understand however, is that repurposing does nothing to avoid plastics manufacturers using virgin stock to make their products. Most of Australia’s claimed 15% ‘recycled plastic’ is more likely to be repurposed into other applications. Only a small amount follows the post-consumer path.

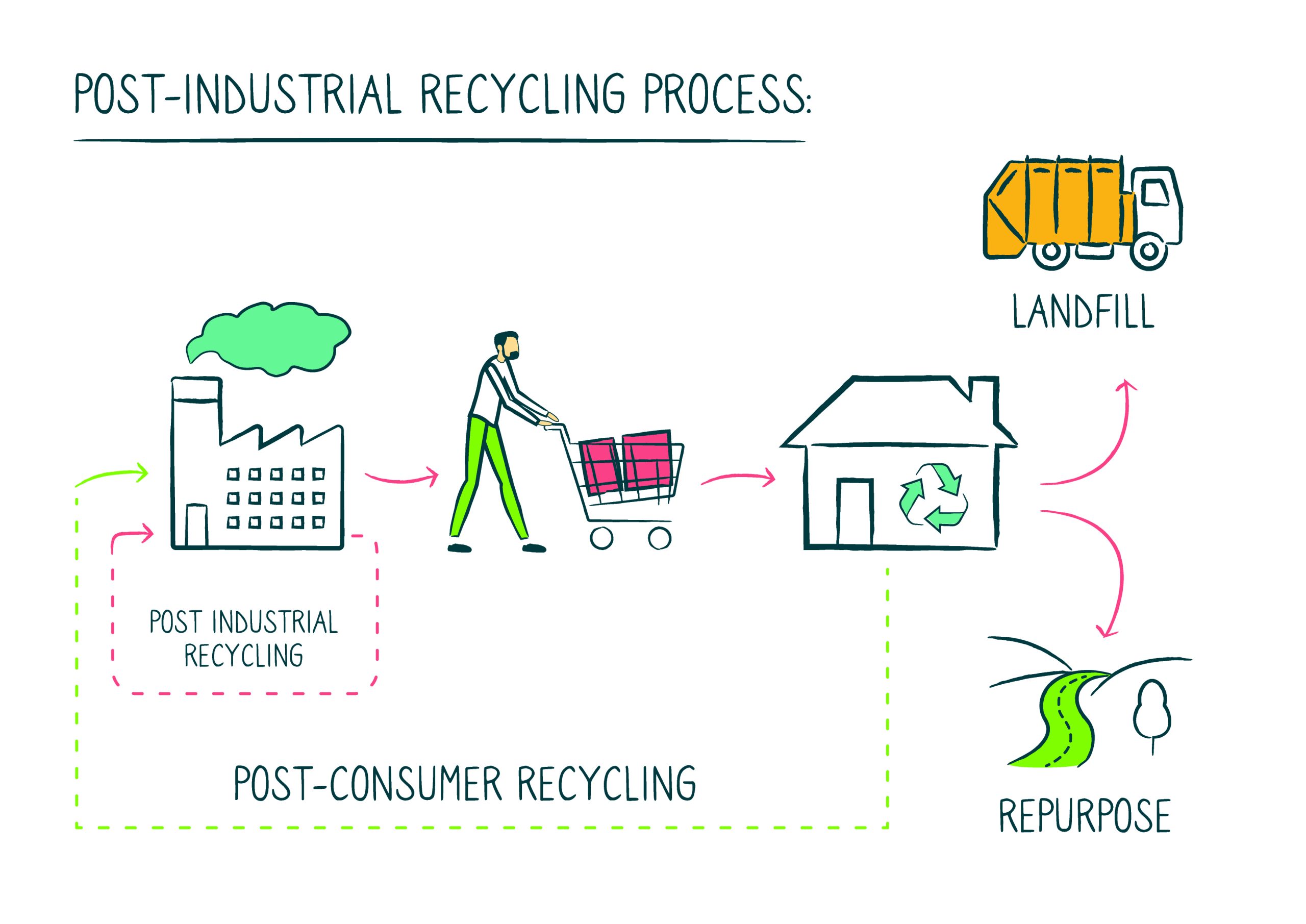

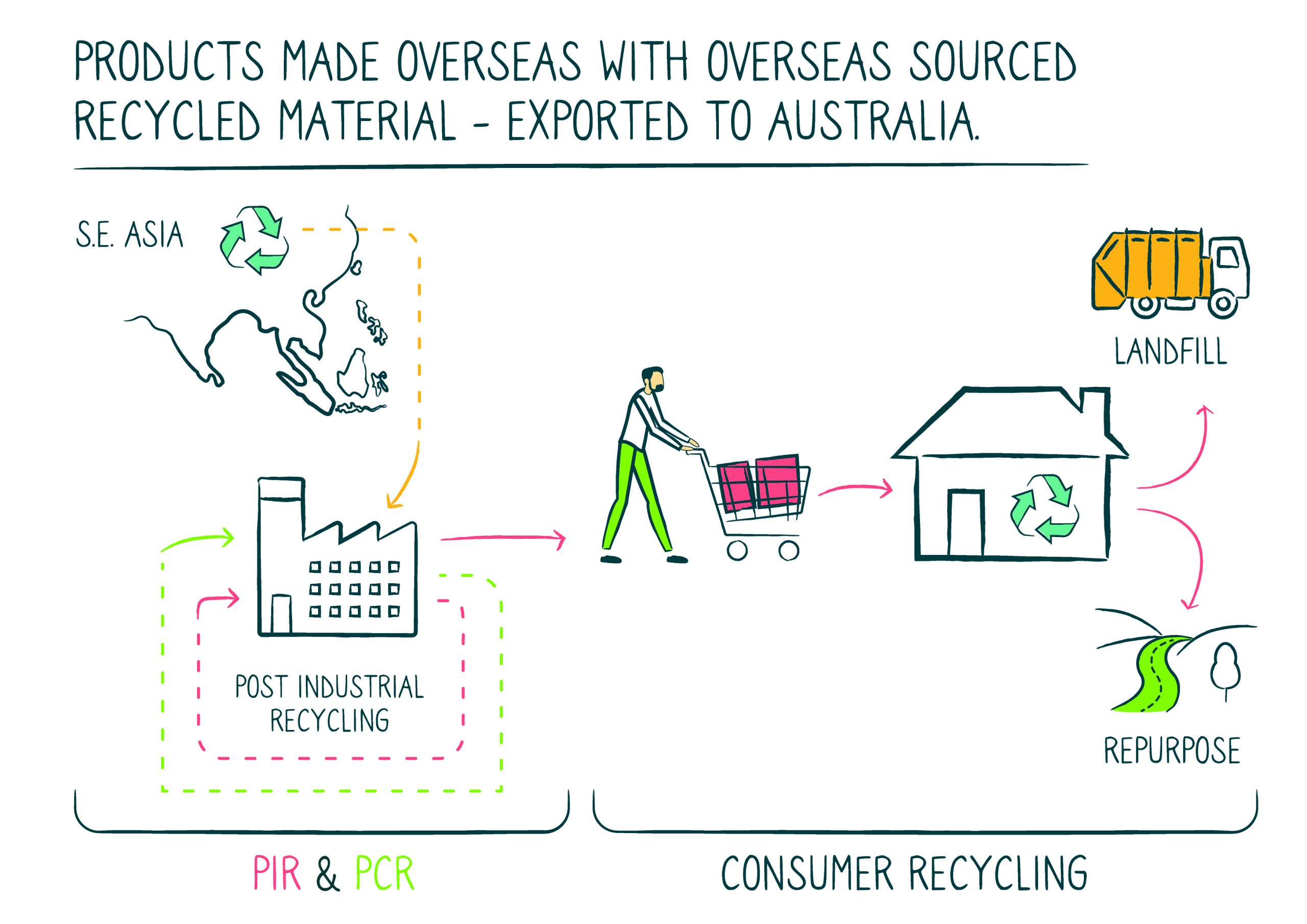

Post Industrial Recycling (PIR) is another term, where material is reclaimed from the internal operations during the plastic manufacturing process and is re-ground back into a form where they can feed it back into their production operations. Industry has rightly been doing this for years to save costs. But now with the big spotlight on recycled material, Post Industrial Recycling is being claimed under the ‘Contains Recycled Plastics’ umbrella. This leads consumers to believe their plastic items are made from other recycled plastic items claimed back from plastic waste streams.

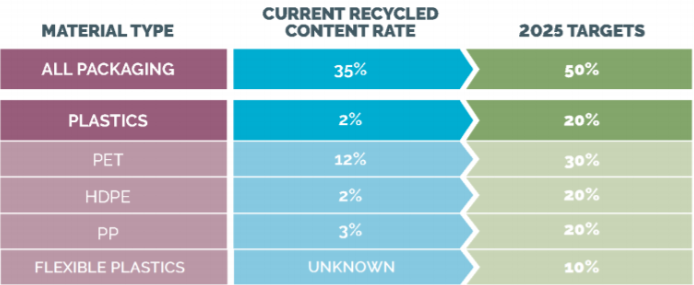

Now to further the complications with the use of the terms ‘recycling’ and the ‘circular economy’ – the government target is for products to contain some designated percentages of recycled material. Here in Australia, a lot of plastic is imported, approximately 4 million tonnes of items a year. However, there is not the manufacturing capacity any more to manufacture all this demand, even if high grade recycled material from Australian waste was available.

Most of these plastic items are imported, and if they are made overseas from overseas sourced recycled material they can still be labelled in Australia as contains recycled content. This is doing nothing to promote the circular economy in Australia. It is furthering the circular economy at a global level which is still a good practice, but it is doing nothing to address Australia’s waste plastic problem.

Further given the increasing demand for products made from Post Consumer Recycled material, we need to be using an international oversight authority such as GRS who certifies the Post Consumer Recycled claim made by these manufacturers is actual Post Consumer Recycled material to avoid greenwashing.

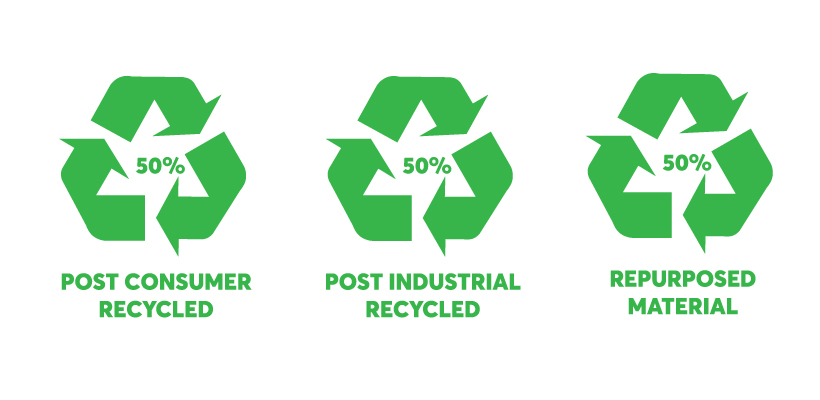

To be transparent to consumers, there needs to be requirements on any claim of container recycled content. These requirements should be labelled as follows should have 3 aspects to it.

- Recycled with Post Industrial Recycled plastic or Post Consumer Recycled plastic

- What percent is recycled plastic

- Domestic or foreign sourced recycled material

Currently, the government goals are 50% recycled content. There is no definition on what that 50% recycled material is. It could be Post Industrial Recycled material, say from China. Then if marketed as ‘Contains recycled plastic’ in Australia, that product is doing little to drive actual recycling of waste material in Australia. Consumers would think they are doing a good thing by preferencing those purchases. If there were these standard and transparent definitions of what the ‘Recycled’ material was it would go a long way to driving meaningful recycling in Australia, avoid consumer confusion, and most importantly avoid greenwashing.