Author: Dr. Ross Headifen (PhD)

Ross Headifen has a PhD in Mechanical Engineering and has 28 years of experience developing sustainable and environmental industry products. Ross is co-founder of landfill biodegradable plastics brand Biogone and environmental equipment supplier FieldTech Solutions.

When the news broke of REDcycle suspending its operation of soft plastic collection in November 2022, it was a shock leaving many of us feeling let down and asking what are we supposed to do now? REDcycle has been doing us all a big favour these last few years, letting us dispose of soft plastic guilt free. We bought it, then disposed of it thinking it was being recycled into other products, we were ‘wish-cycling’ and thought were doing the right thing.

REDcycle was only collecting 3 percent of soft plastics of the roughly 250,000 tonnes used in Australia annually. So perhaps we should first consider what is going on in the world of soft plastic recycling in Australia, as the bigger problem is the lack of infrastructure and little demand for its repurpose.

Plastic recycling and the circular economy

The idea of recycling is for a product to be made and used, then for the waste materials to be sent back to the manufacturer for another new similar product to be produced. This is what we now call the circular economy. In a perfect circular economy, there would be no need to import any more virgin materials into the loop, as the materials go around and around.

For products like a metal cans the circular economy works well, and the metal can be circulated indefinitely. Metal can be melted down and re-cast into its new shape with the exact same material properties as the previous use. Recycling of glass is similar. With plastics however, the concept of a circular economy is not so circular. There are many barriers to recycling this material. A piece of plastic waste cannot be simply heated up, re-melted, and formed into a new shape like a bag, food wrapper, film etc.

Plastic recycling limitations

For years, the only recycling option for plastics was mechanical recycling, where the plastic was shredded up into little flakes and then downcycled into a more basic low-tech product like a park bench or roads. This could happen up to three times before the plastic molecule was so damaged that it no longer provided the strength properties necessary, and after its last use it would also need to be disposed of. Unfortunately, mechanical recycling is just delaying the inevitable that eventually the plastic will still need to be disposed to landfill.

Plastics are made in many colours, with many different additives, combined in laminates and blends. They have historically been designed for functionality for single use, not for recycling purposes, which makes them very difficult to be re-purposed into use for other products. Plus, if a waste plastic product is downcycled each round, then it is not stopping the manufacturing of the original product being made from virgin materials, it is always encouraging the manufacturers to buy more new material to make their products.

Repurposing vs. Recycling

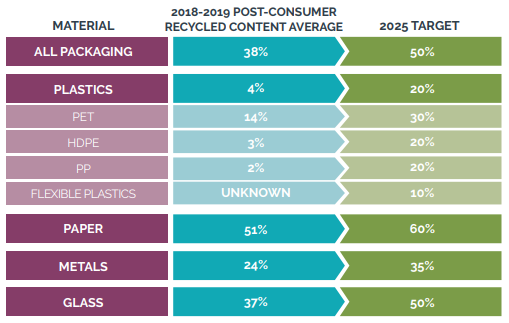

The government goal in the 2025 National Packaging Targets is only 10% of soft plastics sold to be recycled. The government includes ‘re-purposing’ as recycling, so in effect much less plastic will be recycled to displace virgin material for manufacturing use. In the case of REDcycle, their biggest acceptor of recycled plastic waste was a company re-purposing the plastic into roads. This would be for a single use purpose and would never be used again. It is not what we think of as recycling, but more of a one-time re-purpose and is not participating in the circular economy.

Figure: APCO – Australia’s 2025 Recycled Content Packaging Targets and annual progress

Another issue for soft plastics is the lack of infrastructure available to collect the plastic waste from the end user and transporting it back to a recycling facility, for plastic this is particularly difficult. Think about all the consumer related plastic packaging – food wrappers, shopping bags, drink cups, coffee cups, bottles and more. Expecting the user to carry them to an appropriate recycling station instead of disposing of them is a big expectation in the first place. There are no monetary incentives for the consumer to recycle their soft plastic waste either, such as the container deposit scheme offering a 10-cent refund.

Many consumers are also not sufficiently educated and are confused on how to correctly recycle their plastic waste, and most soft plastic cannot be put into kerb side recycling bins either. Attempts at decades of education on what can be recycled and policy around collection practices have had very limited success, as the quality of recycled materials collected in Australia is relatively poor compared to other countries.

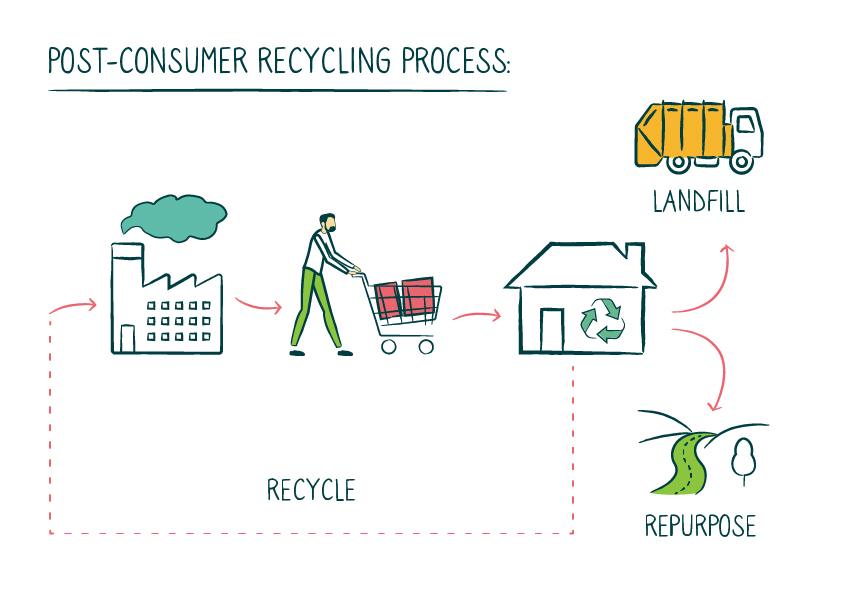

For plastic recycling, unfortunately most plastic is either sent to landfill and a small proportion is repurposed, while an even smaller proportion is going around the recycling path to support a circular economy.

Figure: Post-Consumer Recycling Process

Post-Consumer vs. Post Industrial Recycling

The idea of recycling needs to be separated out to the two forms it takes. Post-Consumer Recycling and re-using Post-Industrial materials.

Post-Consumer Recycling

Post-consumer waste materials such as paper, cardboard boxes, empty plastic bottles and aluminium cans are used in the post-consumer recycling process, which are often collected by local recyclers and brought to recycling facilities, sorted into bales of like material, then sold to be reprocessed and remanufactured into other products. This is what we all think when we see the words ‘made with recycled materials’ on the label.

Figure: Post-consumer recycled materials

Post-industrial materials

In Post-industrial recycling, the waste plastic from producing a product in a factory, is re-ground in the factory or another facility, then taken back to the production line to be used again. For example, when plastic is blown into bottles, the scrap waste or cut offs that are left behind are kept and, re-pelletized, to be used again.

Figure: Post-industrial plastic waste materials to be re-ground

Post-industrial recycling has been performed for many years to save costs and was never really promoted under modern day recycling parlance. The material never sees any consumer use, but with the ever-increasing pressure to make it appear more than it is, it’s often promoted as recycling now too. This is misleading to consumers, as they would assume that recycling percentages on packaging refer to their own post-consumer plastic waste being recycled, not post-industrial plastic waste.

Figure: Recycling pathways – Post-consumer recycling vs. Post-Industrial recycling

When a product is labelled as being made of recycled materials – it should be required to stipulate as being of Post-Industrial or Post-Consumer content to clearly identify the source of the recycled material.

Recycling of Energy

Another way that recycling is now being considered is for residual plastic that can’t be reclaimed then recycling of its embodied energy. Plastic can be considered as a source of solid fuel. If plastic waste were to be collected and put though a Waste to Energy plant or products are made to specifically biodegrade in a landfill, the embodied energy in the plastic can be released and depending on collection efficiency, this energy can be harnessed to produce electricity or a heating source. According to the National Waste Report 2018, 76% of Australian household waste is going to landfills with methane gas recovery, and 55 landfills in Australia are generating renewable electricity.

So, what next?

Australia unfortunately does not currently have the internal resources to recycle all our plastic waste and to re-purpose it. If we are going to get serious about recycling of soft plastic, we need to advocate for more resources and encourage manufacturing using post-consumer recycled materials, and advocate for better recycling infrastructure in Australia so we can support organisations like REDcycle.

Until we have a solution to deal with the soft plastic waste problem, we need to cut down our requirement for this type of plastic and reduce our waste where possible. Australia can follow the lead of the EU and the UK who have introduced a tax on consumer-packaged goods companies on the production and import of plastics made from less than 30% recycled material. This will discourage companies from continuously producing and importing virgin plastic materials and encourage plastics to be recycled back into the circular economy.